The Science of Feeling like an Outsider

Why we all feel like we don't belong (and what to do about it)

I had a surprising conversation with one of the moms at my daughter’s school this morning. We don’t know each other well, but things got deep fast. I love when this happens.

We began the conversation with an observation that emotions seem contagious, especially around children. She then told me about last week's parent-teacher conferences, where something interesting happened.

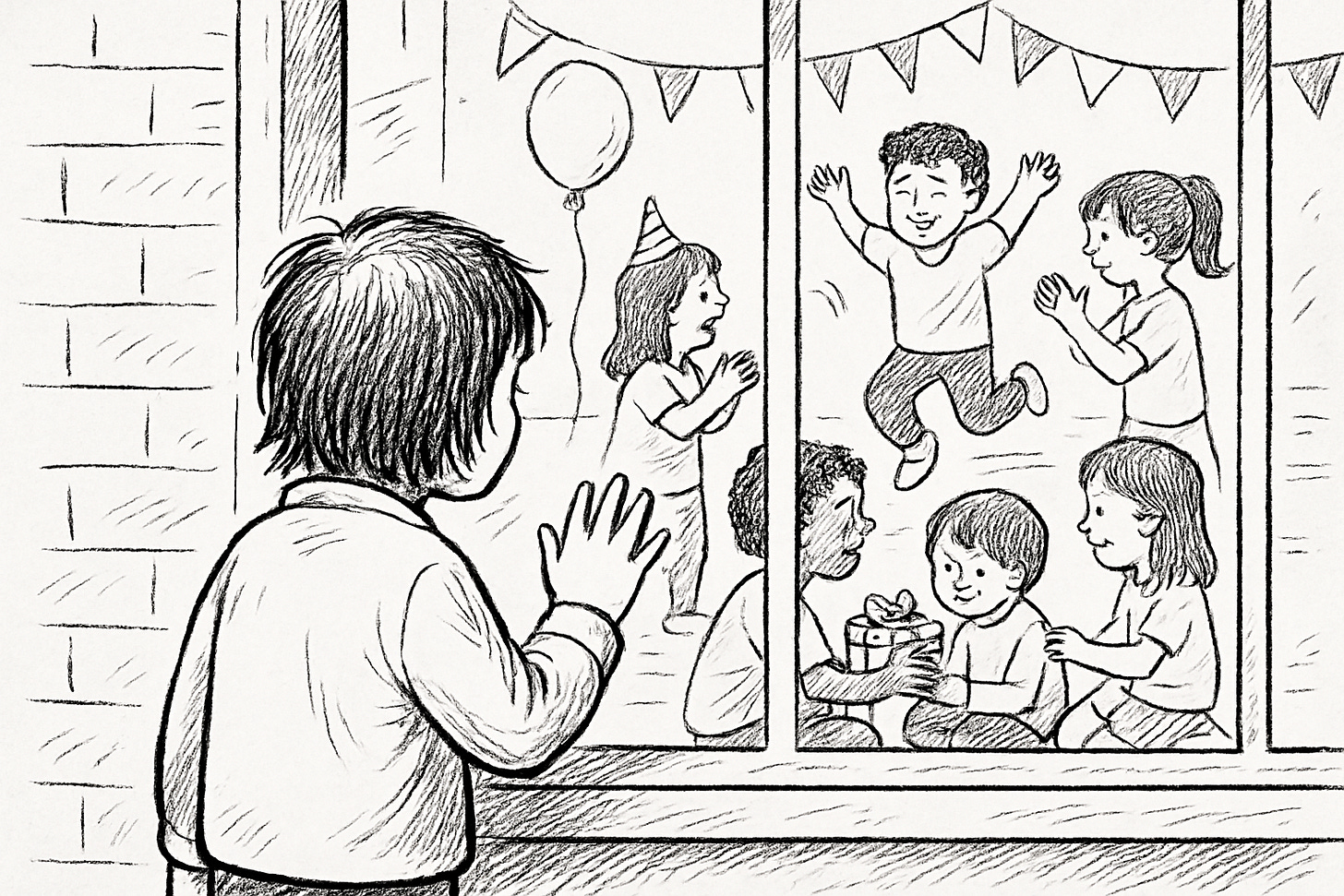

One parent bravely shared that their child feels like an outsider, like they don't fit in. Soon, every parent in the room was commenting in recognition—all of their children feel exactly the same way.

What struck me most was the context: this is happening at our Waldorf school, widely considered one of the best in the country. These children are remarkably kind, collaborative, and well-behaved. There's very little bullying. They're explicitly taught about love and community. And yet, nearly all of them feel like outsiders.

If you're reading this thinking, "I feel that way too," I already know that's true. Not because I'm being presumptuous, but because almost all of us are wired to feel this way.

In my psychology studies, I've been diving deep into interpersonal neurobiology (IPNB)—a field that explores how our relationships shape our brains. IPNB emerged partly as a counterpoint to the individualistic psychological theories that dominated the late 20th century.

Those earlier theories—which shaped everything from our economic systems to parenting philosophies—were based on a fundamental misunderstanding: that human wholeness comes from complete independence. We were told that maturity means not needing anyone else. Children were pushed toward independence far too early, with the well-meaning but misguided belief that this would lead to optimal mental health.

Neuroscience has now demonstrated that this approach wasn't just wrong—it was actively harmful.

As Dr. Amy Banks explains in her book Wired to Connect, our brains have a neural network specifically designed for connection. A region called the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) activates both when we experience physical pain and when we feel social rejection. This overlap is no accident—our brains evolved to experience social disconnection as literally painful because our survival as a species depended on maintaining strong social bonds.

When our early relationships don't support healthy connection—whether through explicit rejection or through subtle cultural messages that dependence is weakness—this neurological wiring leads us to feel perpetually like outsiders. We become hyper-vigilant to signs of rejection, even when they aren't there.

This explains the paradox of our society: we celebrate individualism while simultaneously creating endless products, services, and content aimed at helping us fit in. It's why those parents in the meeting recognized their children's feelings immediately—because they feel the same way themselves.

It's worth noting that feeling like an outsider isn't all bad. So much of the world's art, music, and innovation has come from people channeling their sense of not belonging into creative expression. The countercultures and movements that have advanced society often began with those who embraced their outlier status.

The answer isn't that we all become the same. The answer is understanding that we can be connected despite—even because of—our feelings of difference. It's not a pain we overcome through sameness, but through genuine connection.

Here's more good news: our brains are remarkably plastic. As Dr. Dan Siegel discusses in Aware, neuroplasticity allows us to reshape our neural pathways throughout our lives. He describes how mindful awareness practices can actually alter the physical structure of our brains, helping us develop what he calls "integration"—the linkage of different parts of ourselves into a harmonious whole. This rewiring begins at the individual level.

When I shared all of this with my mom friend in the parking lot, she asked what this process could look like. I shared my own experience: In just a few months of targeted work to address this specific neural wiring in myself, I've watched that painful feeling of being an outsider begin to dissolve.

What's interesting is that it wasn't replaced with some triumphant feeling of being the ultimate insider. Instead, that painful belief simply faded, replaced by a general sense of contentment and belonging, alongside a deeper compassion for others who I now recognize are experiencing the same struggle.

This transformation has changed how I relate to everyone from my daughter to the strangers I encounter, knowing they likely carry the same insecurities I've known so intimately. It also inspired me to return to writing and to actively grow my coaching practice, recognizing that I can help create these changes in others, which will ultimately benefit their own communities, and so on. Over time, the potential upside is infinite, and it can start with only one person.

I told my mom friend that our conversation was a perfect example—by acknowledging this universal feeling of disconnection, we created a moment of genuine, deeper connection, and to imagine what would happen if more of the parents began connecting on a deeper level.

If you're feeling left out, please know that it's just your brain playing tricks on you, and that there are actual practices that can override the neural networks in your brain and provide healing.

Some simple practices that can begin rewiring these neural networks include regular moments of genuine connection (even brief conversations like the one I had this morning), mindful awareness of your belonging in the present moment, and intentionally noticing when your brain tries to tell the “outsider story” so you can gently redirect it. This can literally look like telling yourself, the moment you feel the feeling, that “this is my dACC playing tricks on me.” Even something as simple as making eye contact and smiling at strangers can activate your brain's connection circuits in ways that gradually change these patterns.

If you’d like to dig deeper into this work, reading Dr. Amy Banks’ Wired To Connect is a great place to start.

Ironically, the feeling of being an outsider is the one thing everyone has in common. What you think you're suffering from individually is actually a universal experience that binds us all together. This realization alone changed my brain, and I hope it does the same for you too.

H

This reminded me so much of the philosophy of "The solution lies within the problem" and a book by Henri Nouwen called "The wounded healer."

Every single day, I am newly amazed about what can happen when we tell the person beside us what is happening inside of us.