I'm writing this from Joshua Tree, where I'm enjoying some quiet time, as well as doing some research and self-reflection.

Today, I'd like to write about a pattern I've been reflecting on this week. It's not only a pattern I deal with personally, but it's a pattern I’m working on with almost all of my clients, and it's a pattern that powers Silicon Valley.

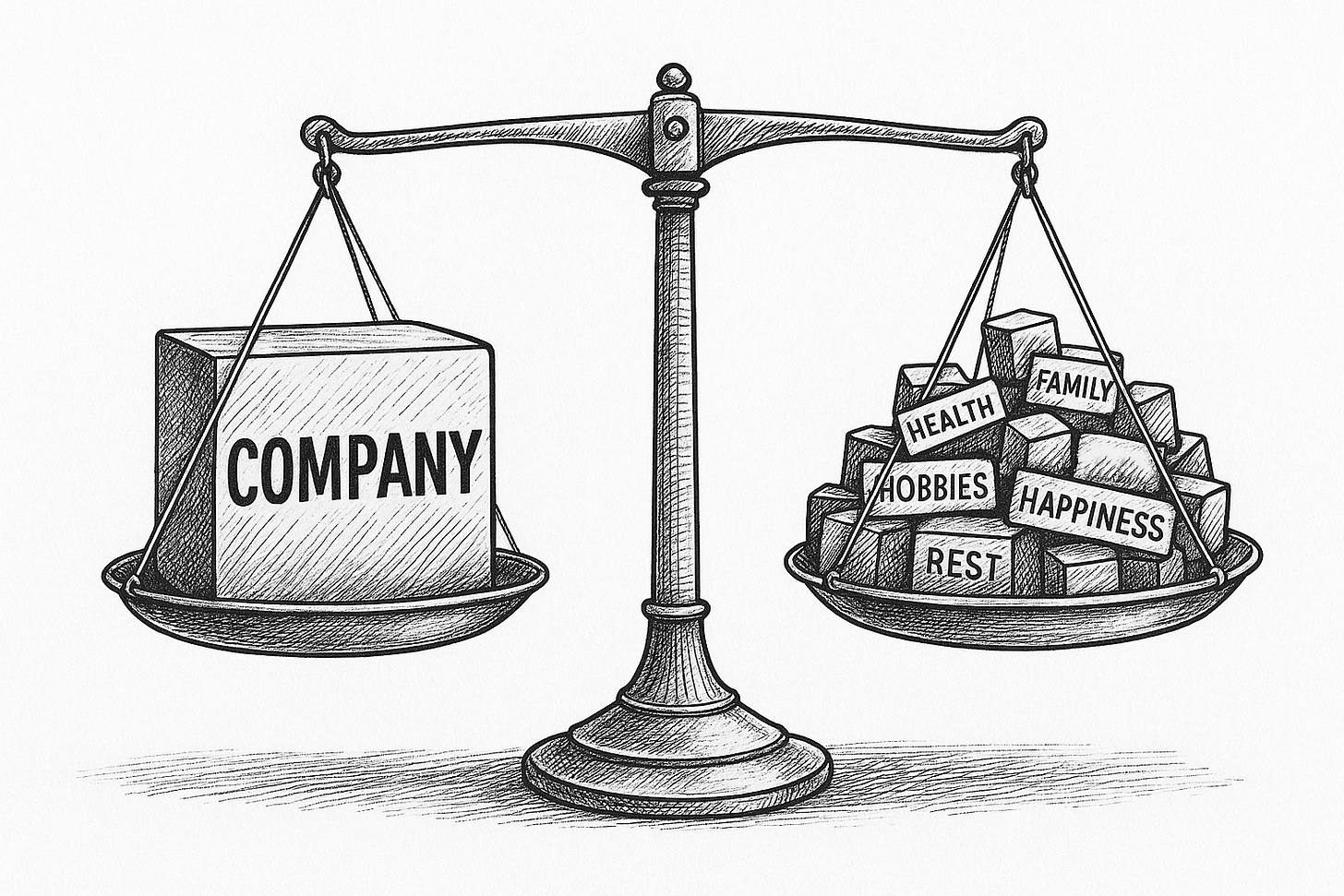

It's the idea that when you go "all-in" on something, you will maximize your return.

Investors can already see the fault in this argument, but most of us engage in this pattern more often than we think.

A few examples I know of from my own personal network:

The founder who gives all of their time to their company, sacrificing their social life, marriage and family

The professional athlete who gets injured at the peak of their career and didn't prepare for the loss of income and identity

Layoffs impacting the Silicon Valley PM who has spent 10-20 years working their way up the management ladder only to be dismissed as "redundant" today

The senior engineering or design specialist whose skills have quickly been replaced by AI

As a founder, it tends to go like this: you got to where you are by giving everything to your career. And now, at the helm, everything falls on you. So if you're not putting 100% into your startup, then it's on you if it doesn't work out. There is always more to do, and so even your all is never enough.

I personally felt this pressure when I was a founder, and I learned the downsides of going all-in through personal experience.

But to be clear: the solution isn't the opposite of this—to half-ass, or to only half-commit, or distract yourself with more things.

Neither is the solution to simply "balance your life." If it was easy, founders would already be doing it. There are often underlying patterns that make this lifestyle shift nearly impossible.

The Culture That Created This

If you're someone who defaults to "all-in" mode, it's worth understanding why. Often, this pattern starts early. Many of us learned as children that our worth was tied to our achievements—that love and approval came through performance or perfection, not through simply existing.

Silicon Valley has essentially systematized the reward of these patterns, creating a culture that selects for and funds people who demonstrate this level of self-sacrifice. For years, we've romanticized founders who sleep under their desks, make huge personal sacrifices, and broadcast their hustle on social media.

But here's what these narratives leave out: most startups fail regardless of founder dedication. Even the ones that sell often don't generate significant returns for founders. Instead you have health crises, broken marriages, and high-profile founders who tell me privately they feel like they have no real friends.

The Tides are Turning

Even if the "all-in" approach once made economic sense, it definitely doesn't now. We're living through rapid technological change, economic volatility, and industry disruption. The specialists—people who went all-in on one skill, one industry, one way of thinking—are often the ones getting hit hardest by layoffs and AI displacement.

Meanwhile, there's a growing trend, especially in younger generations, toward "portfolio careers"—deliberately cultivating multiple streams of work, income, and creative expression.

When "All-In" Becomes Self-Sabotage

I recently worked with someone who is dealing with this pattern. He has founded multiple companies in various life cycles and has an investment portfolio that requires his attention. Despite his success, he recently confessed to me that he believed he was failing everyone because he couldn't give enough time to any single venture. He felt like he was letting everyone down.

His guilt was eating him alive, and ironically, that stress was making him less effective across all his ventures as well as impacting his ability to be a confident leader.

After getting to the bottom of the belief systems driving this behavior, we did something simple but revelatory: we audited every entity and project—business and personal—that required his time and attention. Then we calculated what percentage of his bandwidth he could realistically dedicate to each.

The breakthrough came when we discussed how many successful people operate exactly this way. Investors manage dozens of portfolio companies. Serial entrepreneurs often lead multiple ventures simultaneously. Many successful people choose to make time for family, because they realize they are the authority on their schedules. And, most crucially, they have the stamina to do all of this because they have set appropriate boundaries and their lives are in balance.

When he communicated his actual availability to each of his teams—being honest about what percentage of his time they could expect—he was met with relief. Instead of the scattered, guilty energy he'd been projecting, his teams now saw someone who was intentional and in control. They could plan around his schedule rather than constantly wondering about his priorities.

What Integration Actually Looks Like

Over the last few years, I've been deliberately shifting my own life into more of a portfolio approach. Not long ago, my entire life revolved around one company. Now, part of my life is spent as an executive coach, part of it is getting a master's in psychology, part of it is doing creative work, part of it is motherhood, part of it is health, and so on.

These different areas inform and benefit each other, and I engage with each one on my own terms. Coaching only takes up a fraction of my life, for instance. Going all-in on it wouldn't benefit me in the ways I desire—especially if it's at the expense of my health or building the balanced life I aspire to maintain.

Choosing to be in graduate school for psychology, which also represents just a fraction of my time, makes me a better coach than going "all-in" ever could. My studies provide me with better frameworks for understanding my clients' challenges. But again, it's not everything. My operational background, personal experiences, and even motherhood provides crucial context for the entrepreneurial struggles I'm seeing in the founder community.

True integration isn't about perfect balance—it's about allowing different parts of yourself to coexist and enhance each other. Some seasons, one area might demand more attention. But the goal is learning to occasionally prioritize one area while maintaining balance.

A Different Way Forward

If you recognize yourself in the "all-in" pattern, here's what I'd suggest: Start by doing what my client did. Audit every aspect of your life that requires attention—your business, your health, your relationships, your personal growth, your finances. Be honest about what percentage of your bandwidth each area actually needs and deserves.

Then, notice any hesitation. The counterarguments happening in your head are often belief systems preventing you from making changes. Where do they come from? Who taught them to you? Examining these patterns is crucial to making the changes you desire.

When you're ready, communicate these new boundaries clearly. Your team will likely be relieved to know exactly when they can expect your attention rather than constantly wondering if they're bothering you, or wondering where you are. Your family will appreciate knowing where you stand as well.

Even if you're currently running just one company, remember that you are the boss—you ultimately have the power to design your life. A more balanced, empowered approach will benefit all areas of your life, including your career.

One last thing: I am opening up one more spot in my coaching practice. If my work resonates with you and you’d like to explore working together, just reply to this email.

Until next time,

H